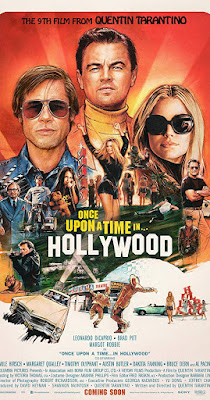

Quentin Tarantino's Stillborn Alternate History: "Once Upon a Time...in Hollywood"

Quentin

Tarantino’s new film, Once Upon a Time…in

Hollywood has received widespread attention in recent weeks, with many

critics singling out the film as a work of alternate history.

To a

degree, these characterizations are accurate.

The film

portrays Charles Manson’s “family” members failing to kill actress Sharon Tate (and

four of her friends) as well as Leno and Rosemary LaBianca in the summer of

1969. Instead, the “family”

members target Tate’s actor/stuntman neighbors (played by Leonardo DiCaprio and

Brad Pitt), but promptly meet with a grisly end. (Cue flamethrower).

Because

history unfolds differently, the appellation “alternate history” is accurate.

Yet, it

would be more precise to describe the film as a “stillborn alternate history.” That is to say, it promises to portray

history taking a different course without actually doing so. It offers a fascinating protasis

(cause), but offers little by way of an apodosis (effect).

Tarantino

did the same thing in his film, Inglourious

Basterds, which depicted Hitler’s assassination in Paris leading to an

earlier end to World War II. Yet,

the film did little to explore the possible ramifications of this alteration to

history’s course.

There’s

nothing wrong, of course, with Tarantino flirting with – but failing to commit

fully to – the genre of alternate history.

But it

does raise the interesting counterfactual question of what he might have done,

had he been inclined to show the full consequences of how American life would

have been different without the Tate/LaBianca murders.

Consulting

a 2017 New Yorker article

by Jeffrey Toobin on the Manson murders yields some interesting possibilities.

Toobin writes

that “In media, in criminal law, and in popular culture, Manson created a

template that, for better or worse, is still familiar today.”

He argues

that it was not the Tate-LaBianca murders in and of themselves that changed

America, but the media spectacle that it unleashed.

Toobin

writes that “although cameras were not allowed in courtrooms at that time, it

helped create the demand for them. Manson had a dark charisma, and he enjoyed

the attention. The trial was such a sensation that President Richard Nixon pronounced

Manson guilty before the jury had gone out.”

The lead

prosecutor in the case, Vincent Bugliosi’s subsequent book, Helter Skelter “helped create the

true-crime genre, which remains a publishing institution.”

Toobin

adds that

“The

Manson “Family” both anticipated and inspired the growth of sinister cults in

American life, especially in California. In the decade that followed the Manson

murders, the Symbionese Liberation Army kidnapped Patty Hearst, in Berkeley,

and Jim Jones’s Peoples Temple, in San Francisco, transfixed supporters, more

than nine hundred of whom committed mass suicide in Guyana.”

“Before

Manson, it was more or less a given that criminals chose to associate with one

another in gangs or in crime families. But Manson told the world that people

became criminals through the influence of others as well. Our fascination with

Stockholm syndrome and brainwashing owes much to what the world saw in the

Manson case.”

So if we

subtract the Manson murders from American history, what are we left with?

In a

nutshell, a more innocent, less crime-obsessed country.

This, of

course, begs the question of whether some subsequent killing would have filled

the place of the Manson murders had the latter never happened. Whether Son of

Sam, or any of the figures portrayed in the Netflix show, Mindhunter, it is possible that other killers would have become the

new “Manson” of American life.

(For that matter, Manson himself might have gone ahead and order another

killing at some point afterwards in the wake of the failure to murder Tate).

Had any

of these things come to pass, the absence of the Tate-LaBianca murders would

ultimately have functioned as a reversionary counterfactual, in the sense that

America’s ‘descent into a crime obsessed country would have happened

deterministically one way or the other.

Not a

very comforting thought.

Comments