Friedman's Counterfactual Comparison of ISIS and Vietnam

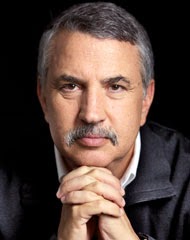

In his recent New York Times column, Tom Friedman draws parallels

between the United States’ developing campaign against ISIS and its ill-fated

battle against communist forces in Vietnam.

In the attempt to provide a

boost to the former, he highlights the shortcomings of the latter, writing:

“It’s a long, complicated

story…but a big part of it was failing to understand that the core political

drama of Vietnam was an indigenous nationalist struggle against colonial rule —

not the embrace of global communism, the interpretation we imposed on it.

The North Vietnamese were both communists and nationalists — and still are. But the key reason we failed in Vietnam was that the communists managed to harness the Vietnamese nationalist narrative much more effectively than our South Vietnamese allies, who were too often seen as corrupt or illegitimate. The North Vietnamese managed to win (with the help of brutal coercion) more Vietnamese support not because most Vietnamese bought into Marx and Lenin, but because Ho Chi Minh and his communist comrades were perceived to be the more authentic nationalists.

I believe something loosely akin to this is afoot in Iraq. The Islamic State, or ISIS, with its small core of jihadists, was able to seize so much non-jihadist Sunni territory in Syria and Iraq almost overnight — not because most Iraqi and Syrian Sunnis suddenly bought into the Islamist narrative of ISIS’s self-appointed caliph….They have embraced or resigned themselves to ISIS because they were systematically abused by the pro-Shiite, pro-Iranian regime of Bashar al-Assad in Syria and Prime Minister Nuri Kamal al-Maliki in Iraq — and because they see ISIS as a vehicle to revive Sunni nationalism and end Shiite oppression.”

At this point, Friedman lays the framework for an interesting counterfactual:

“Obsessed with communism, America intervened in Vietnam’s civil war and took the place of the French colonialists. Obsessed with jihadism and 9/11, are we now doing the bidding of Iran and Syria in Iraq? Is jihadism to Sunni nationalism what communism was to Vietnamese nationalism: a fearsome ideological movement that triggers emotional reactions in the West — deliberately reinforced with videotaped beheadings — but that masks a deeper underlying nationalist movement that is to some degree legitimate and popular in its context?

I wonder what would have happened had ISIS not engaged in barbarism and declared: “We are the Islamic State. We represent the interests of Syrian and Iraqi Sunnis who have been brutalized by Persian-directed regimes of Damascus and Baghdad. If you think we’re murderous, then just Google ‘Bashar al-Assad and barrel bombs’ or ‘Iraqi Shiite militias and the use of power drills to kill Sunnis.’ You’ll see what we faced after you Americans left. Our goal is to secure the interests of Sunnis in Iraq and Syria. We want an autonomous ‘Sunnistan’ in Iraq just like the Kurds have a Kurdistan — with our own cut of Iraq’s oil wealth.”

That probably would have garnered huge support from Sunnis everywhere….”

Friedman goes to explain why, then, ISIS has been so ideological extreme, concluding that it reflects the leadership’s recognition that its jihadi-nationalist alliance may, in fact, be quite tenuous. In answer to the question “why did ISIS behead two American journalists?”, Friedman writes: “Because ISIS is a coalition of foreign jihadists, local Sunni tribes and former Iraqi Baath Party military officers. I suspect the jihadists in charge want to draw the U.S. into another “crusade” against Muslims — just like Osama bin Laden — to energize and attract Muslims from across the world and to overcome their main weakness, namely that most Iraqi and Syrian Sunnis are attracted to ISIS simply as a vehicle of their sectarian resurgence, not because they want puritanical/jihadist Islam. There is no better way to get secular Iraqi and Syrian Sunnis to fuse with ISIS than have America bomb them all.”

The North Vietnamese were both communists and nationalists — and still are. But the key reason we failed in Vietnam was that the communists managed to harness the Vietnamese nationalist narrative much more effectively than our South Vietnamese allies, who were too often seen as corrupt or illegitimate. The North Vietnamese managed to win (with the help of brutal coercion) more Vietnamese support not because most Vietnamese bought into Marx and Lenin, but because Ho Chi Minh and his communist comrades were perceived to be the more authentic nationalists.

I believe something loosely akin to this is afoot in Iraq. The Islamic State, or ISIS, with its small core of jihadists, was able to seize so much non-jihadist Sunni territory in Syria and Iraq almost overnight — not because most Iraqi and Syrian Sunnis suddenly bought into the Islamist narrative of ISIS’s self-appointed caliph….They have embraced or resigned themselves to ISIS because they were systematically abused by the pro-Shiite, pro-Iranian regime of Bashar al-Assad in Syria and Prime Minister Nuri Kamal al-Maliki in Iraq — and because they see ISIS as a vehicle to revive Sunni nationalism and end Shiite oppression.”

At this point, Friedman lays the framework for an interesting counterfactual:

“Obsessed with communism, America intervened in Vietnam’s civil war and took the place of the French colonialists. Obsessed with jihadism and 9/11, are we now doing the bidding of Iran and Syria in Iraq? Is jihadism to Sunni nationalism what communism was to Vietnamese nationalism: a fearsome ideological movement that triggers emotional reactions in the West — deliberately reinforced with videotaped beheadings — but that masks a deeper underlying nationalist movement that is to some degree legitimate and popular in its context?

I wonder what would have happened had ISIS not engaged in barbarism and declared: “We are the Islamic State. We represent the interests of Syrian and Iraqi Sunnis who have been brutalized by Persian-directed regimes of Damascus and Baghdad. If you think we’re murderous, then just Google ‘Bashar al-Assad and barrel bombs’ or ‘Iraqi Shiite militias and the use of power drills to kill Sunnis.’ You’ll see what we faced after you Americans left. Our goal is to secure the interests of Sunnis in Iraq and Syria. We want an autonomous ‘Sunnistan’ in Iraq just like the Kurds have a Kurdistan — with our own cut of Iraq’s oil wealth.”

That probably would have garnered huge support from Sunnis everywhere….”

Friedman goes to explain why, then, ISIS has been so ideological extreme, concluding that it reflects the leadership’s recognition that its jihadi-nationalist alliance may, in fact, be quite tenuous. In answer to the question “why did ISIS behead two American journalists?”, Friedman writes: “Because ISIS is a coalition of foreign jihadists, local Sunni tribes and former Iraqi Baath Party military officers. I suspect the jihadists in charge want to draw the U.S. into another “crusade” against Muslims — just like Osama bin Laden — to energize and attract Muslims from across the world and to overcome their main weakness, namely that most Iraqi and Syrian Sunnis are attracted to ISIS simply as a vehicle of their sectarian resurgence, not because they want puritanical/jihadist Islam. There is no better way to get secular Iraqi and Syrian Sunnis to fuse with ISIS than have America bomb them all.”

Friedman’s counterfactual works

relatively well in isolating and identifying one of the causal forces

underpinning ISIS’s rise to prominence: secular Sunni nationalism.

At the same time, the counterfactual

is implausible on the face of it, insofar as there is little likelihood that

ISIS would have ever been able to make a non-ideologically radical appeal of

the kind Friedman proposes. What

defines ISIS is precisely its ideological fanaticism, which cannot be seen

merely in utilitarian terms.

There is a clear precedent in Nazi

Germany. Although many adherents

of the NSDAP supported the party for diverse reasons, we should not lose sight

that Hitler and Nazi core leadership was fanatically committed to an

ideological agenda.

As long as the leaders of tyrannical

groups behave in accordance with strict ideological principles – and as long as

they remain in charge -- we cannot expect their “moderate” allies to exert much

of a modulating effect.

Comments