The “Clockstopper” Counterfactual and the Holocaust

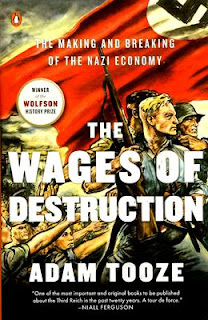

Recent historical writing on

the Holocaust has been filled with different kinds of counterfactual

observations. (I discuss them at

length in a forthcoming book on the memory of Nazism). Let me offer a preview by profiling one interesting type: the “clockstopper” counterfactual.

In his recent award-winning

book, The Wages of Destruction

(2007), historian Adam Tooze devotes several pages to discussing the Nazis’ brutal

policies against the Slavs during World War II, especially the regime’s

decision to allow over 3.3 million Soviet POWs to die of starvation. In this context, Tooze makes the counterfactual claim that “if the clock had been stopped in early 1942, this

programme of mass murder would have stood as the greatest single crime

committed by Hitler’s regime,” exceeding that of the Holocaust (p. 483).

Interestingly, Tooze’s claim

echoes an older one made by historian Christopher Browning in his book, The Path to Genocide (1992). In his preface (p. ix), Browning wrote:

“If the regime had disappeared in the spring of 1942, its

historical infamy would have rested on the ‘war of destruction’ against the

Soviet Union. The mass death of some two million prisoners of war in the first

nine months of that conflict would have stood out even more prominently than

the killing of approximately one- half million Jews in that same period.”

Both Tooze’s and Browning’s observations

initially appear convincing, but they are ultimately weakened by the arbitrary

quality of their counterfactual premise. In order to be convincing, a counterfactual turn of events

must have a certain degree of plausibility. By failing to explain how

World War II would have suddenly stopped -- or how the Nazi regime might have

disappeared -- in 1942, Tooze’s and Browning’s points have a decidedly artificial

and unconvincing feel to them.

It hardly merits noting that if one “stops

the clock” on any process, historical or otherwise, its outcome and ultimate

significance are altered. (To be

glib, if we take the soufflé out of the oven halfway through its

cooking time, it fails to become a soufflé).

There is no denying that our understanding

of the Nazis’ crimes will be determined by the point at which we measure them. Browning, indeed, illustrated this fact

earlier on the same page of The Path to

Genocide when he turned the clock back even further in time and observed, “If the Nazi regime

had suddenly ceased to exist in the first half of 1941, its most notorious

achievements in human destruction would have been the so-called euthanasia

killing of seventy to eighty thousand German mentally ill and the systematic

murder of the Polish intelligentsia.”

In other words, we would not view the murder of Soviet POWs as a

horrific crime because it would not yet have taken place.

But this point is obvious. The question is not whether

an event’s significance will be shaped by the point at which one stops the

clock and measures it. The

question is whether any such clockstopping was likely to take place to begin

with. If not, then the

counterfactual has a tendentious quality to it.

Comments