Anselm Kiefer's Counterfactual Art

It’s rare to be able to

comment about counterfactual thinking in the visual arts. For obvious reasons, it’s difficult to

visually portray historical events transpiring differently in a single

image. (This is why book covers

for works of alternate history are often so predictable, the default move being

to alter obvious symbols, like postage stamps, flags, or national monuments, to

signify a historical change of some kind – see for instance, the cover image on

Philip Roth’s The Plot Against America).

A new exhibition

of paintings by Anselm Kiefer at the Gagosian Gallery in New York City,

however, offers an opportunity to see how “what if?” thinking can influence art. Kiefer’s exhibition is entitled “Morgenthau

Plan” and invokes the infamous never-enacted plan, conceived by US Treasury

Secretary Henry Morgenthau in 1944, to punish Germany after the end of World

War II by pastoralizing and de-industrializing its economy. As is well known, President Franklin D.

Roosevelt never approved the plan and U. S. Military Government officials quickly

embraced a more reconstructionist occupation policy already by 1946.

Nevertheless, the question

has always hovered over postwar German history: what if the Morgenthau Plan had

been implemented? More than a few

German writers have explored the premise in fictional form, most notably Thomas

Ziegeler, in his novel Die Stimmen der

Nacht (1984), and Christoph

Ransmayr, in his novel, Morbus Kitahara

(1995). Their texts portray Germany never being able to emerge

from its wartime devastation and becoming a seething hotbed of rightwing

resentment against Allied “vengeance.”

In so doing, the texts expressed doubts about the virtues of memory by

showing how the desire to hold the German people accountable for the Nazis’

crimes backfires by leading to a nightmarish outcome for the Allies and Germans

alike.

It is hard to say whether

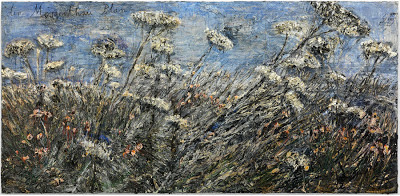

Kiefer’s artworks offer the same conservative message. Most of the paintings

are bleakly decorative works featuring flowers against cold gray (and

occasionally blue) backgrounds of postwar devastation. Without the titles to aid the viewer’s

understanding of the painter’s intentions, the works would have no

counterfactual meaning whatsoever.

With them, they invoke --

but add little depth to -- the familiar idea that the Morgenthau Plan would

have transformed Germany into a premodern agricultural society.

Whether or not Kiefer

believes this would have been a good or a bad thing is unclear. The most the artist has said about the Morgenthau

Plan is that it was a “flawed” idea that “ignored the

complexity of things" (quoted from the exhibition's press release). Most probably, Kiefer meant to suggest that while

the moral impulse behind the plan – punishing perpetrators – was intuitively

sound, the actual punishment would have been counterproductive.

That said, the title of one painting, “Morgenthau Plan: Laßt tausend Blumen Blühen, “Let a Thousand Flowers Bloom,” suggests that Kiefer may empathize with the plan’s spirit. By combining an allusion to Mao’s famous phrase about letting a hundred flowers bloom (theoretically denoting a stance of tolerance) with the historically-burdened number 1,000 (from the Thousand Year Reich), Kiefer might be implying that the flowers of Germany's postwar Morgenthauian landscape would have been the inevitable – and perhaps just? -- byproducts of the Nazi experience.

Whether or not this is the intended message, Kiefer's paintings are clearly provocative. By inverting the traditional symbolism of flowers and associating them with the ugliness of war rather than the beauty of nature, he forces us to rethink our preconceived notions about the world. Still, it remains somewhat frustrating that Kiefer gives us few signs about how he ultimately views the Morgenthau Plan. Especially because the plan has been exploited by right wing Germans eager to relativize their country's Nazi past (by implying that the Allied plan would have brought profound suffering to the German people) -- and especially since Kiefer long ago was questioned about the political wisdom of flirting with Nazi iconography in his photographs and paintings -- were are left to speculate.

Speculating about the painter's intentions is surely appropriate given the speculative theme of the exhibition. But the difficulty in arriving at any clear answers about Kiefer's views of the Morgenthau Plan highlights the limits of painting compared to literature as a medium for exploring alternate pasts.

That said, the title of one painting, “Morgenthau Plan: Laßt tausend Blumen Blühen, “Let a Thousand Flowers Bloom,” suggests that Kiefer may empathize with the plan’s spirit. By combining an allusion to Mao’s famous phrase about letting a hundred flowers bloom (theoretically denoting a stance of tolerance) with the historically-burdened number 1,000 (from the Thousand Year Reich), Kiefer might be implying that the flowers of Germany's postwar Morgenthauian landscape would have been the inevitable – and perhaps just? -- byproducts of the Nazi experience.

Whether or not this is the intended message, Kiefer's paintings are clearly provocative. By inverting the traditional symbolism of flowers and associating them with the ugliness of war rather than the beauty of nature, he forces us to rethink our preconceived notions about the world. Still, it remains somewhat frustrating that Kiefer gives us few signs about how he ultimately views the Morgenthau Plan. Especially because the plan has been exploited by right wing Germans eager to relativize their country's Nazi past (by implying that the Allied plan would have brought profound suffering to the German people) -- and especially since Kiefer long ago was questioned about the political wisdom of flirting with Nazi iconography in his photographs and paintings -- were are left to speculate.

Speculating about the painter's intentions is surely appropriate given the speculative theme of the exhibition. But the difficulty in arriving at any clear answers about Kiefer's views of the Morgenthau Plan highlights the limits of painting compared to literature as a medium for exploring alternate pasts.

Comments

http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b01jgj0p

This link on the other hand discusses a similarly disturbing topic, the Nazi nature protection policy, which in my opinion also could be seen as connected to Kiefers work.

http://www.haaretz.com/jewish-world/jewish-world-features/brown-and-green-were-the-nazis-forerunners-of-environmental-movements-1.513354

http://www.zeithistorische-forschungen.de/Portals/_zf/documents/pdf/2012-1/Uekoetter_2007.pdf